It was May 1997, and Sam Okudzeto, then a member of the African Regional PolioPlus Committee from Ghana, was flying to Sierra Leone for what he anticipated would be a routine annual meeting about polio eradication in Africa. But when his plane touched down and he looked out the window, he saw that soldiers, guns drawn, had flooded the tarmac.

As Okudzeto made his way to passport control, he asked an airport official what was going on. "Listen carefully," he was told. "You can hear the guns." There had been a coup that morning.

"All we heard was boom, boom, boom," Okudzeto recalls. "Then I realized that the aircraft that had brought us had gone."

With no taxis running, Okudzeto and the other meeting participants who had been on the plane walked to a nearby hotel. "We all went to our rooms and put our luggage down and then went to the restaurant," he recalls. "I asked for the biggest and juiciest sole fish I had ever had in my life, because it might be my last supper." (Luckily it wasn’t, and four days later, Okudzeto and the others caught a helicopter out of the country.)

"There is an enemy in life — and it’s fear," he says now. "For those who are not afraid, it’s amazing what you can do. It’s fantastic to see the result now: Africa is [wild] polio-free."

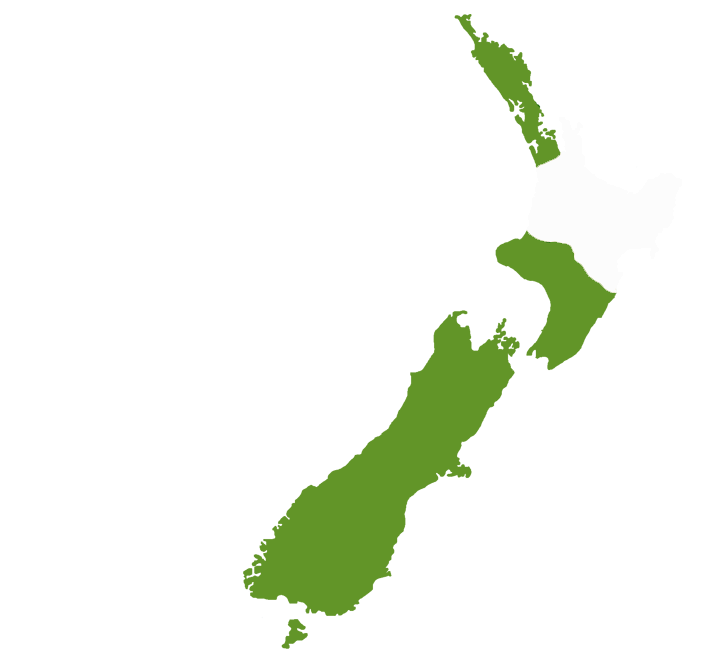

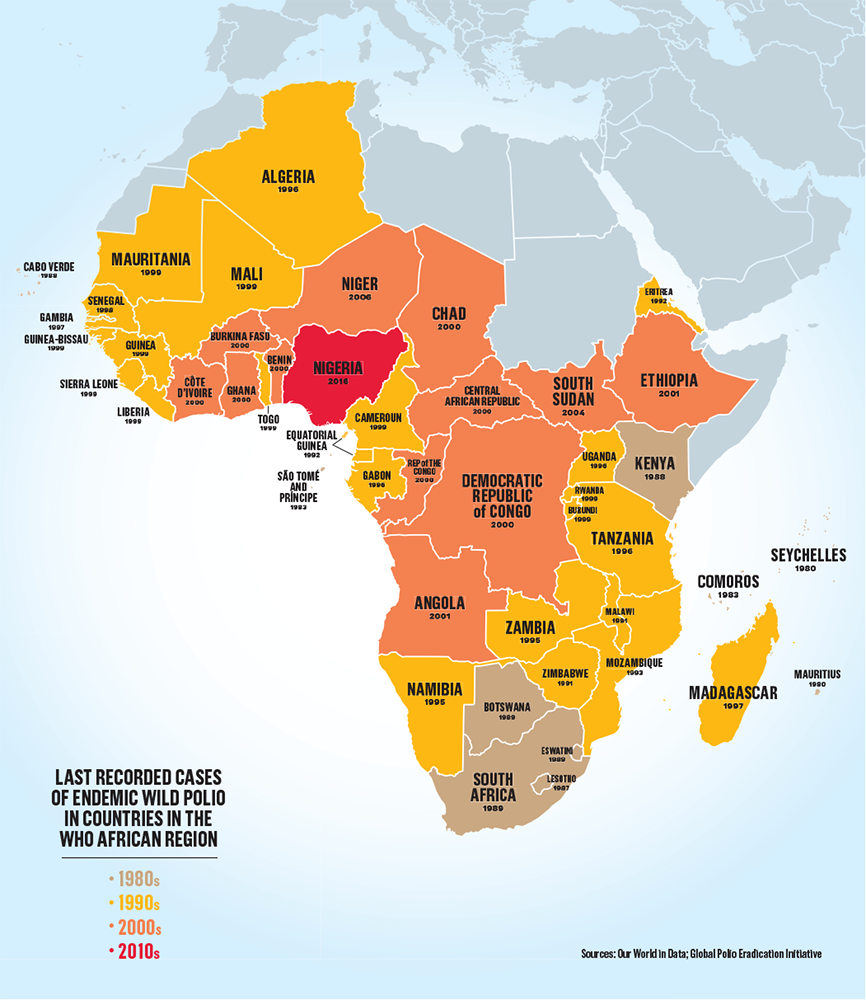

In August, the World Health Organization (WHO) certified the African region free of wild poliovirus, the culmination of a decades-long effort involving millions of Rotary members, health workers, government officials, traditional and religious leaders, and parents. Since 1996, a year when wild polio paralyzed an estimated 75,000 children across Africa, health workers have given more than 9 billion doses of the oral polio vaccine, preventing 1.8 million wild polio cases.

"Everybody chipped in," says Gaston Kaba, longtime chair of the Niger PolioPlus Committee (he retired from the position in June 2019). "Volunteers, town criers, many other people were involved. Nobody knows about them. They worked quietly to get the job done."

The 47 countries that make up WHO’s African region are home to nearly 1,400 Rotary clubs and 32,000 members, many of whom have dedicated time and resources to the effort. Rotary members around the world have contributed nearly $890 million toward eradicating polio in the region, advocated for support from their governments, mobilized communities around National Immunization Days, and held events for World Polio Day to raise public awareness.

The legacy of those efforts is a health care infrastructure that is playing an important role in the COVID-19 pandemic and is poised to respond to future public health emergencies. The laboratory and surveillance networks developed to track the poliovirus are being used to monitor other diseases. Polio workers bolster an array of routine immunizations, deliver deworming medicines and oral rehydration salts, and provide other health services. And they continue to vaccinate children against polio, because until the virus is eradicated from the earth, it remains a threat everywhere. "Being declared free of polio is an amazing success," says Teguest Yilma, Ethiopia PolioPlus Committee chair. "I am happy — but I’m still not relaxed."

In a time of extraordinary challenges, we can celebrate the eradication of wild polio in the African region. Here are just a few of the stories of the drive and determination Rotary members and our partners have shown in overcoming challenges and setbacks.

THE CHALLENGE: Conflict

Viewable Image - rotary and its partners worked to negotiate

Image Caption

Rotary and its partners worked to negotiate truces and military protection for health workers in conflict areas. Tony Karumba/AFP via Getty ImagesIn February 2005, as civil war raged through Côte d’Ivoire, Marie-Irène Richmond-Ahoua entered the heart of rebel-held territory. Then the national Polio-Plus committee chair, Richmond-Ahoua joined representatives from Rotary’s partners on a United Nations (UN) flight to Bouaké, where the rebels were based. "We met with rebel chiefs to beg them to make immunization days safe," she recalls, asking for their cooperation in providing soldiers to protect the vaccinators. "They did it. For five days, it was easy to reach children."

Over the years, security was one of the biggest challenges to the polio eradication effort in Africa. Rotary and its partners worked to negotiate truces and military protection to make sure that health workers could reach every child in conflict areas. In 1994 and 1996, the rebel Sudan People’s Liberation Army and the Sudanese government agreed to honor "corridors of peace" where vaccinators could travel safely, and two years later, a PolioPlus grant supported the airlifting of vaccines into villages that hadn’t seen a government health worker in 15 years. In 1985 in Uganda, the government and the National Resistance Army agreed to permit UNICEF flights into rebel-held territory after the civil war cut off a third of the population from government services. And in late 1999, then-UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan negotiated a nationwide truce in Sierra Leone so that National Immunization Days could be held.

But at times, bloodshed still derailed polio eradication efforts. Nigeria thought it had seen its last case of wild polio in July 2014. But then the militant group Boko Haram kept vaccinators out of its strongholds in Borno state in northeastern Nigeria for several years. "Boko Haram was against immunizations in the first place, so many health facilities were destroyed. Immunization was not even something you could think about," says Tunji Funsho, who has served as Nigeria PolioPlus Committee chair since 2013. Polio was festering, undiagnosed, in the areas of Borno where children hadn’t received their vaccines, and in 2016 the country recorded four cases.

But the Nigerian government — as well as Rotary, its partners, and health workers and volunteers — never gave up. The Nigerian Army became a key participant in vaccination efforts. At first, it would secure an area, and vaccinators would spend two days or less quickly immunizing children before leaving, a strategy called "hit and run." Later, armed local militia members would escort vaccinators to unsafe areas. Today, army medical corps members carry the vaccine to settlements that remain unsafe for civilians to enter and vaccinate children themselves. "The military knows how to take care of themselves," Funsho says.

Funsho recalls visiting the home of the child who had the last case of wild polio in Nigeria, another innocent victim of the insurgency. "The potential for a three-year-old girl in Borno state to achieve the best that is possible for her life is already very low — educationally, socially, in all aspects of human endeavor," he says. "Add polio paralysis to that, and what is the hope for that child? It is heart-rending."

THE CHALLENGE: Rumors

Viewable Image - rotary members in nigeria advocated with government

Image Caption

Rotary members in Nigeria advocated with government leaders and educated the public to dispel persistent myths about vaccine safety. Diego Ibarra SánchezIn Nigeria, another significant obstacle was the persistent rumors about the safety of the oral polio vaccine that spread in the northern part of the country in the early 2000s, Funsho says. Skeptical political and religious leaders told parents to refuse vaccinations, combining rhetoric of the anti-vaccine movement with conspiracy theories about a Western plot to sterilize Muslims. "This rumor was not homegrown. It came from abroad and found local weapons to energize it," Funsho says. "It led to vaccination becoming a political thing rather than a means to protect our children against paralysis."

The situation deteriorated. Several states in northern Nigeria canceled all immunization activities until officials could show proof that the vaccine was safe, and the country went 14 months without a National Immunization Day. The Nigerian government, strongly committed to polio eradication, set up a committee that included key Muslim leaders to verify the vaccine’s safety. They toured vaccine manufacturing sites and produced a report that satisfied all except political and religious leaders in Kano state, the epicenter of the rumors. Officials there sent their own committee of health experts and religious scholars to Indonesia, where they reconfirmed the safety of a vaccine manufactured in a Muslim country.

Meanwhile, Rotary members continued to engage in advocacy and in educating the public. Ado Bayero, the late emir of Kano, was a supporter of the Rotary Club of Kano, and Funsho was his personal physician. One of the country’s most influential Muslim leaders, the emir "was a great friend of Rotary," Funsho says. "He knew Rotary would not bring anything harmful." The emir demonstrated his faith in the oral polio vaccine by personally immunizing his grandchildren in his palace. "We used that to a lot of our advantage in the media."

In neighboring Niger, a country whose population is 99 percent Muslim, then-President Mamadou Tandja pushed back against the persistent rumors in a key speech that launched a 2004 immunization campaign. He gave the speech in Hausa, a language widely spoken in Niger as well as Nigeria, which made his message about the importance of vaccination all the more effective. "Tandja was very strong on the message he delivered," says Kaba, the former Niger PolioPlus Committee chair. "He referred to the Quran. You don’t joke with the Quran." A month later, Rotary presented Tandja with a Polio Eradication Champion Award.

Polio cases in Africa had been trending down until the early 2000s. But the rumors and missed immunizations led to the exportation of the virus from Nigeria to almost 20 countries. "As soon as we overcame that, the graph just went gradually down and down until we got to zero," Funsho says.

THE CHALLENGE: Hard-to-reach children

Viewable Image - to eradicate wild polio in africa

Image Caption

To eradicate wild polio in Africa, health workers had to vaccinate hard-to-reach children such as those at this camp for internally displaced people in northern Nigeria. Andrew EsieboNearly 800,000 refugees live in Ethiopia, most of them from Eritrea, Somalia, and South Sudan. "Our borders are very porous. A lot of people come in and out from neighboring countries," Yilma says. So the government coordinates cross-border vaccination campaigns with surrounding nations to ensure that the virus isn’t brought in over the border.

The country has some of the most rugged terrain in Africa — from mountainous highlands to vast desert plains that sit hundreds of feet below sea level. There are some places where health workers have to walk hours to reach a single family, and others that are so densely populated that ensuring that every child is vaccinated can be difficult. "Ethiopia didn’t face a situation like in Nigeria where people outright refused to be vaccinated," Yilma says. "The problems in Ethiopia are that it’s a large population that is mobile and that the topography of Ethiopia makes them very difficult to reach."

Throughout the African region, millions of health workers have traveled by foot, boat, bicycle, and bus during the decades-long eradication campaign. Grants from The Rotary Foundation have supported them along the way. In 2000, Africa’s first synchronized multicountry immunization campaigns reached 76 million children in 17 countries.

Rotary members from other countries often came to Ethiopia to volunteer during National Immunization Days, providing a morale boost to local members and communities. The visitors saw other needs as well and stepped up to help, Yilma says, supporting water projects and schools in addition to polio eradication.

Related health initiatives — the "plus" in PolioPlus — went a long way toward getting local communities to accept the polio vaccine, says Funsho. During polio outbreaks in Nigeria, children were visited frequently by health workers to provide immunizations, yet often families didn’t have clean drinking water or access to basic medicines. Grants from the Foundation allowed Rotary members to install solar-powered boreholes, first in settlements for displaced persons in Borno and later in surrounding communities. "That endeared Rotary to the area," Funsho says.

THE CHALLENGE: Political will

It was 1996. Wild polio would paralyze 75,000 children across Africa that year. A decade earlier, African health ministers had agreed to a goal to reach 75 percent of children with vaccines by 1990 — but the gains they had made were erased in the face of a deteriorating regional economy, lingering drought, competing health priorities, and debilitating civil wars. Polio eradication needed a champion.

Rotary and its partners found one in Nelson Mandela. Approached by Rotary leaders, Mandela, then president of South Africa, agreed to advocate for the cause. At the July 1996 summit of the Organization of African Unity (the predecessor to the African Union), Mandela galvanized his fellow African heads of state to make polio eradication an urgent priority. Within weeks, Mandela, with Rotary leaders by his side, launched the Kick Polio Out of Africa campaign, using soccer matches and sports stars to rally support. By the end of the year, more than 30 countries had held National or Subnational Immunization Days, and 60 million children had been vaccinated. "The involvement of the African Union, particularly of Mandela, meant so much for us," Okudzeto says. "It was fantastic."

Rotary members used their respected roles in society — and often their personal charisma — to advocate for their governments to become active in polio eradication. "Security and political will were the biggest challenges," says Richmond-Ahoua, the Côte d’Ivoire PolioPlus Committee chair from 1996 to 2014. "We have to convince civic society, opinion leaders, parents, traditional leaders, and religious leaders. Ending polio was not an option; it was an obligation."

Such advocacy work wasn’t glamorous; it involved regular meetings with ministers of health and their staff members to remind them that poliovirus was still there. And sometimes Rotary members had to get creative to convince recalcitrant leaders that it was their responsibility to immunize the citizens of their country. Richmond-Ahoua tells a story about this.

It was 2000, and there had been a coup in Côte d’Ivoire. The new government didn’t want to carry out National Immunization Days. Richmond-Ahoua decided to go to the head of state’s home — without an appointment.

Upon arrival, she asked to see the wife of General Robert Guéï, who had been put in charge after the coup. "They looked at me as if I was mad," she says. "But Rotarians take risks when they want some-thing." After waiting more than five hours, she was finally called in to see the first lady, Rose Doudou Guéï. When she explained why she was there, the first lady was in complete agreement, and she not only convinced her husband of the importance of the NIDs, but attended one herself. "She’s a woman. She has children. She understood," Richmond-Ahoua says.

Richmond-Ahoua’s story is one dramatic example of the everyday advocacy by Rotary members to keep polio at the top of the political agenda in countries throughout the continent. Though now Africa is wild polio-free, the work will continue, Richmond-Ahoua says. "We have to ensure that the political will is strong to finish the job."

Kaba recalls looking at a map of Niger with Tandja, the country’s president from 1999 to 2010. "Niger is a huge country, the size of California and Texas combined, and two-thirds of the country is desert. He said, ‘Can we eradicate polio from this country?’" Kaba remembers. "I said, ‘Yes, with your help, we can.’"